Gramercy Typewriter Company was opened by Abraham Schweitzer in 1932; today it is owned and operated by his son and grandson, Paul and Jay Schweitzer. (Collage by Mollie Suss)

(New York Jewish Week) — Not too long ago, a New Yorker could have purchased a typewriter at any one of a plethora of typewriter stores across Manhattan.

Today, only one survives: The Gramercy Typewriter Company, owned and operated by Paul Schweitzer and his son, Jay Schweitzer.

The Jewish father-son duo are the the second- and third-generation owners of the store, which sells, repairs and reconditions the trusty machines that have been all but eclipsed in the digital age.

The shop also sources typewriters for period movies and Broadway shows, some of the last places where you can still see people tapping away at once ubiquitous Royals, Olivettis and Smith Coronas.

“We were one of countless typewriter shops around the city — if anything, we were one of the smaller ones,” Jay Schweitzer, 56, told the New York Jewish Week.

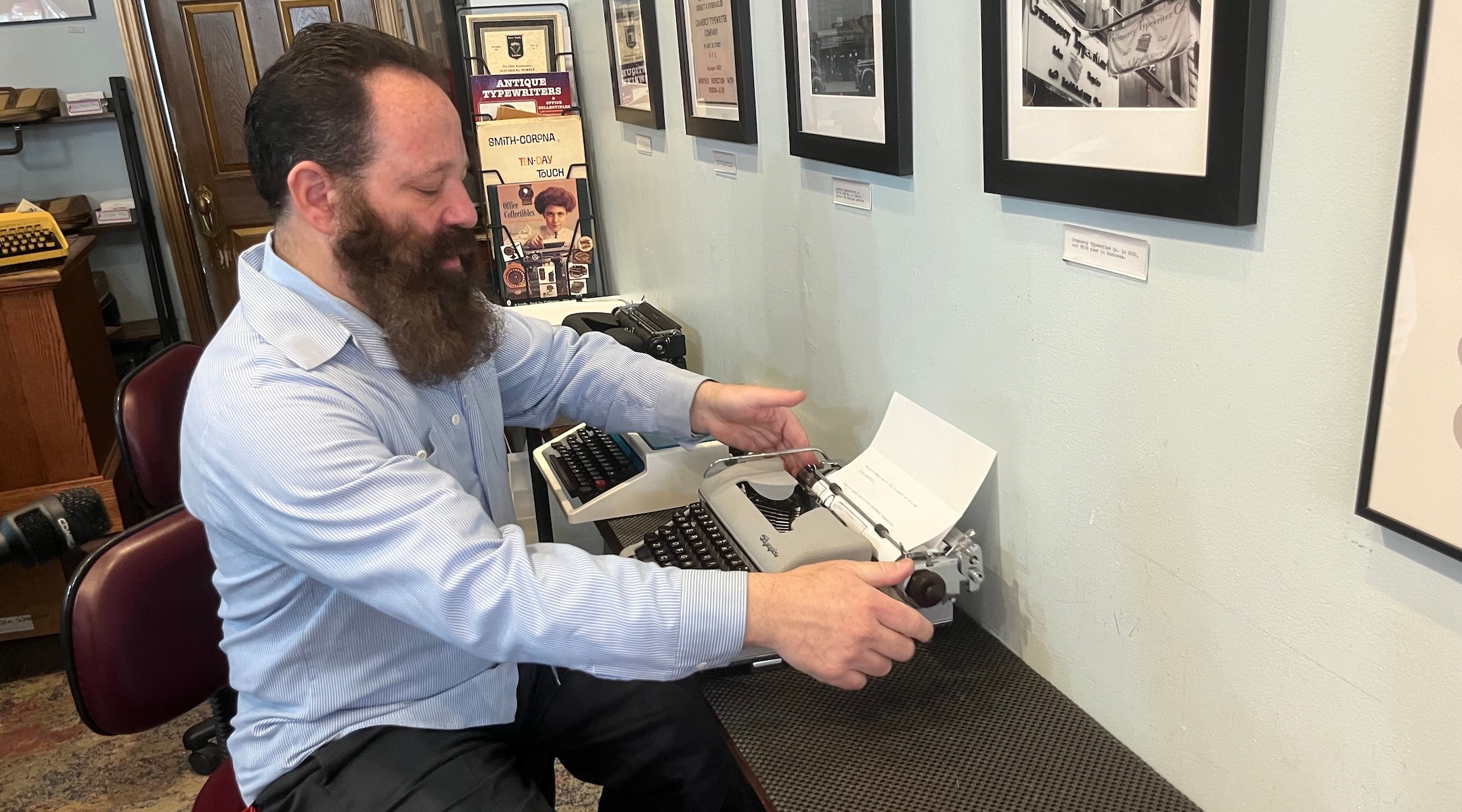

The storefront itself serves as an homage to the history of the business and to the machine, with dozens of vintage typewriters on display, as well as old pictures of the family (pictured is Paul Schweitzer) and vintage posters and advertisements lining the walls. (Julia Gergely)

Gramercy Typewriter Company was opened in 1932 by Abraham Schweitzer — Paul’s father and Jay’s grandfather — who arrived in New York City from Europe sometime in the early 20th century. Ninety-two years later, the store is still in operation.

The unlikely survival of the Gramercy Typewriter Company can be attributed to the Schweitzer family’s dedication to quality and service. Over the years, Jay said, other typewriter stores would approach his father Paul about joining forces — but Paul always declined the offers. “He always felt that he liked it small and personable — he liked getting to know the customers, letting them know you and about your service, and building the business that way,” he said. “Interestingly enough, we’re the only one left and all those big typewriter shops are long gone.”

Abraham Schweitzer became involved in typewriter repair during the Great Depression, when “he was looking for any kind of job he could get,” according to his grandson. “He stumbled across a typewriter shop and he got hired just to clean the floor and help out around the shop.”

“He watched and observed,” Jay added. “Over time, he got more responsibilities and at some point, he felt that he may be better suited to do this on his own.”

According to his grandson, Abraham “got some tools, he got some suits, and he just started going door to door” to service typewriters. Eventually, he built up a small clientele, and needing a place to store some extra supplies and hang his hat, he rented an office space at 40 East 20th St. in Manhattan.

The store has been extant since then, although it has relocated several times — first to a bigger space on West 23rd Street, which Jay said was once known at the “typewriter district,” and then again to another space on 23rd St.

In 1960, the store moved to the Flatiron Building — also on 23rd Street — where it operated for nearly five decades. In 2007, it moved across the street for another decade and a half before finally landing at its current Chelsea location at 108 West 17th Street.

And while the storefront has changed several times, the name, Gramercy Typewriter Company, hasn’t — and neither have their business practices. Just like the wares it sells, the business is mostly analog — the store doesn’t take credit cards and, instead of relying on computers, they mostly use index cards to keep a database of their clients and inventory.

“It’s a tough business — you don’t do it to get rich. You do it because you enjoy it,” Jay said. “I enjoy it, my dad still enjoys it. He must, because he’s still working after doing this for about 65 years. It’s the only job he’s ever had. Hopefully, I’ll head down that same path.” (Julia Gergely)

The family’s Judaism has also been passed down for generations, Schweitzer said. “It’s always been an important part of my life,” he said, adding that he has rich memories of observing the Jewish holidays and attending Hebrew school while growing up in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. “It was just passed down — that’s what my grandparents did, that’s what my mom and dad did and that’s what we’re doing now.”

Schweitzer credits much of the store’s continued success to the work ethic of his father Paul, who is now 86. “It’s because of the good reputation, the quality of work, knowing the customers very well, knowing their needs, providing great service and changing times,” Jay said. “We stuck with what we knew best, and are still thriving today.”

For most of their history, the Schweitzers have made their living servicing broken typewriters, which Paul and Jay currently do in offsite locations in Manhattan and Long Island, repairing about 30 typewriters a week.

However, with hundreds of typewriters in their inventory, customers can make an appointment to talk to Jay or Paul about what type of machine they might be looking for – electric, manual or vintage. Their typewriters start at $245 and can go for up to $1,000.

There is no “typical” client for Gramercy Typewriter Company: Schweitzer counts plenty of authors and screenwriters as customers, as well as hobbyists of all ages trying to get away from the screen for a few hours a day.

About 25 of Gramercy’s typewriters were used in the 2017 film “The Post,” set in a newspaper office in 1971. Director Steven Spielberg then purchased the machines as “wrap gifts” for the cast and crew, including for Tom Hanks, a typewriter aficionado who starred in the film as Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee.

“Paul sells tools, not toys,” superfan Hanks wrote in an email to The Washington Post in 2018. “His typewriters work, and are meant to be used, to be pounded on, to be written with. Typewriters are like pianos — translation objects that artists use to create dreamscapes and shoppers use to make grocery lists. The difference is that whatever you type will physically exist for centuries.”

Another longtime customer is author and journalist Robert Carowho, at any given moment, is writing his epic biography of Lyndon Johnson on the eight or more Smith Corona Electra 210s that he’s purchased from Gramercy Typewriter Company.

The celebrity buzz may be a bonus, but ultimately the store’s core loyal customers are what keep the company in business, Jay said.

“We’ve never had an issue [staying open],” he said. “Of course, it’s not just rent. The cost of doing business in New York City is exuberant and it only continues to go up every year. We’re just grateful that we have a longstanding clientele that still needs our services, combined with a younger generation that is really enjoying using a typewriter. So we continue to work hard every day, and as long as people still need our services, we’re not going anywhere.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.