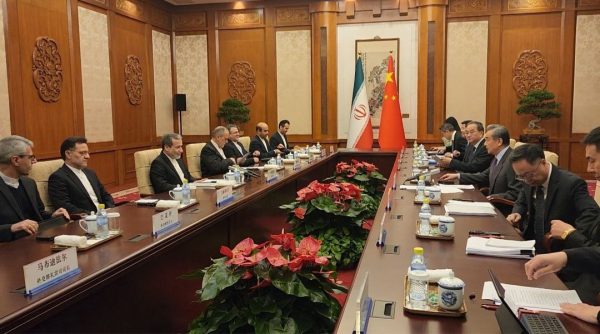

In late December, Iranian Foreign Minister Seyed Abbas Araghchi visited China for the first time since taking up his post. The visit, coming as Iran faces the most severe economic crisis and outside security risks since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, attracted great attention from Chinese netizens. Chinese public opinion included two main strands, both of which were critical of Iran – but for very different reasons.

One line of thinking is that Iran is incompetent and China is tired of being the country’s friend. Amid Araghchi’s visit, a large number of netizens left messages under the social media profile of the Iranian Embassy in China to express both ridicule and protest. Many of these posters advised Iran to develop nuclear weapons to confront the United States and Israel.

The other viewpoint believes Iran’s recent failure in the Middle East shows that its foreign policy is deeply flawed, which has put China’s interests at risk. But rather than advocating for Iran to acquire nuclear weapons, Chinese netizens in this camp advise a different path. They urge Iran to learn from China’s historical experience, change its policies, and avoid military confrontation – believing that this will benefit Iran and also protect China’s strategic interests.

These debates are not new, of course. In 2014, when Araghchi was the deputy foreign minister of Iran, he came to Beijing. Several Chinese reporters, including myself, interviewed him at the Iranian Embassy in China. At that time, the Iranian nuclear issue was an international flashpoint. I asked Araghchi what he thought of the Six-Party Talks led by China to solve the North Korean nuclear issue. Could it provide a model for the Iranian nuclear issue?

Araghchi answered very frankly. He said the Iranian nuclear issue is different from the North Korean nuclear issue, because Iran was not pursuing nuclear weapons.

In Araghchi’s latest visit to China, his first as foreign minister, both sides also talked about the Iranian nuclear issue. This highlights one commonality with the North Korean nuclear question: Both topics have been discussed for over 15 years, but there is still no solution in sight. Moreover, it is very likely that the Iranian nuclear issue will eventually evolve to become more like the situation with North Korea. Amid the gradual weakening of Iran’s proxies in the Middle East, Iran and Israel had two direct military conflicts last year, which have worsened the security environment around Iran. Thus Iran’s determination to develop nuclear weapons as a security guarantee may be greater than ever.

Recently, some media outlets connected to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps have publicly proposed the development of nuclear weapons as a deterrent against Israel and the United States. The topic of acquiring a nuclear capability is no longer taboo issue for Iran, which is dangerous for the world.

Meanwhile, the situation on the Korean Peninsula itself could inspire Iran to follow North Korea’s example. The Six-Party Talks collapsed and the threat of North Korean nuclear weapons is growing. Talk has now turned to arms control rather than denuclearization, and Russia has hinted it could recognize North Korea’s status as a nuclear state. These developments will all encourage Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

Of course, these same dynamics will also prompt Israel and the United States to take military risks against Iran – including by potentially attacking its nuclear facilities. Plans for such strikes were reportedly discussed in the White House late last year. Any conflict involving Iran will have a huge impact on China’s strategic interests in the Middle East.

Although China expressed a positive attitude during the meeting with Araghchi, emphasizing its willingness to expand comprehensive cooperation with Iran, Chinese officials must have felt at least some of the same uneasiness expressed by the country’s netizens. There is widespread concern expressed on Chinese social media that Iran will become another Syria.

In Syria, domestic anger against the Bashar al-Assad regime brought the country into a decade-long civil war. Assad’s regime survived for more than 10 years thanks to the military intervention of Iran and Russia, but finally collapsed last last year.

Today, as the Trump 2.0 era dawns, Iran is unfortunately in its own Arab Spring 2.0 moment. As internal and external pressures mount simultaneously, Iran is facing a severe situation – but no country will send troops to save it. Ali Khamenei is preparing for a successorbut will the Iranian regime be able to last?

For China, the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria was unfortunate, but the damage to Chinese interests is controllable. After all, China has no huge investment in Syria. Iran is a different story. It is an important node of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, and China’s economic cooperation projects in Iran are far greater than those in Syria. In addition, Iran is a foothold in China’s Middle East strategy and one of the few countries that allows China to deeply involve itself in regional affairs.

Thus helping Iran avoid serious risks is very important for China’s strategy. This is not only conducive to the stability of Iran regime, but also crucial for the maintenance of China’s interests.

While some Chinese netizens are openly advocating for Iran to acquire nuclear weapons, this is not something the Chinese government would like to see. On the contrary, China’s own historical experience to get out of a domestic and geopolitical crisis could be an excellent example for Iran, with both positive value and negative lessons.

For years, Iran has supported Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and the Shiites in Iraq. In essence, it is Iran’s version of “exporting revolution,” which was popular in the 1960s and 1970s. During those decades, the Soviet Union promoted the global left-wing movement. Even China had such a policy during the Mao Zedong era, helping communists in Southeast Asia to seize power, as well as some Eastern Europeans to fight against the Soviet Union.

In the 1970s, the best friend China had in Europe was Albania, which Beijing referred to as “a bright lantern” if socialism in Europe. In the era when almost all the Chinese people were hungry, Beijing gave Albania a lot of aid simply because it opposed the Soviet Union.

In another example, the Chinese government backed the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran because it was the Soviet Union’s rival. As a result, Iran was very hostile to China for a period of time after the 1979 revolution. One Chinese diplomat told me that he saw slogans such as “Down with the U.S., Down with Israel, and Down with China” side by side on the streets of Tehran.

In its backing of regional proxies, China in the 1970s echoes Iran’s policy today.

But in China’s case, Deng Xiaoping quickly adjusted the former strategy after Mao’s death. China completely cut off the policy of “exporting revolution.” Instead, Beijing established diplomatic relations with the United States and implemented its “reform and opening up” policy to the West, which led to decades of rapid economic development.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union eventually collapsed. One important reason was Moscow’s insistence on “exporting revolution,” especially via military intervention in Afghanistan.

History is a mirror. Faced with a severe economic situation, Iran should no longer divert its resources to provide money and military aid to proxies in the Middle East. Instead, it should invest this money in domestic livelihood, education, and infrastructure construction to enhance its people’s sense of achievement and happiness. This is a valuable experience of China’s development.

Further following in China’s footsteps, Iran should improve its relations with the United States and Israel, implement the Iranian version of “reform and opening up,” ease relations with neighboring countries, and reduce the influence of ideology on its diplomacy.

After Donald Trump takes office, the Khamenei regime should seize its window of opportunity. With North Korea, Trump showed himself to be open to flexible diplomacy. Abandoning the secret nuclear weapons program, making concessions on this issue, and reaching a new nuclear deal with the United States is a good idea to ensure Iran’s security.

However, to reach a deal with Washington Iran must also adjust its relationship with Israel. I don’t know whether Chinese officials have directly questioned Iran’s policy, but I can tell very clearly that China’s policy toward Israel and Middle East peace is very different from that of Iran.

Iran does not recognize Israel’s right to exist and opposes the two-state solution. But China has labeled relations with Israel as “innovative comprehensive partnership” and supports the two-state solution. Chinese people and officials alike cannot condone Iran’s rhetoric about “wiping Israel from the map.”

Iran says that its support for Palestine is a just cause. But China and Russia also support Palestine, and make friends with Israel as well. Iran does not need to support Palestine by exporting revolution and launching a proxy war with Israel. It is foolish to deliberately create an enemy; it is obvious that Israel has become a source of risk for the Khamenei regime under the current policy.

Of course, Israel also needs to change its Middle East policy, especially its attitude toward Palestine. But it will be easier to prompt Israel to change by becoming friends. Egypt, Jordan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia all see it clearly, and Iran should also understand this point.

In fact, in recent years, China has been preparing for how to safeguard Beijing’s interests in the context of changing situation in the Middle East. Part of this strategy involves paving the way for Iran’s reconciliation with its neighbors.

Last year, I wrote an article for The Diplomat arguing that China’s mediation to improve relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran was actually a part of the strategy to help Iran’s security and keep China’s interests safe. A few months later, China tried to mediate the reconciliation of various Palestinian factions, which is also part of the same strategy to stimulate Iran to change its policy.

In the future, if China can encourage Iran improve its relations with the United States and Israel and prevent possible military strikes from bringing civil unrest to Iran and tensions in the Middle East, that would best serve China’s own interests.

I believe the Chinese government has confidence: Even if Iran improves its relations with the U.S. and Israel, it will not harm China’s interests. After all, China-Iran relations were not affected after the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. In fact, Beijing has always supported a return to this diplomatic achievement, as it reaffirmed to Araghchi during his visit.

If Iran instead chooses to develop nuclear weapons as a misguided attempt to cope with internal and external pressure, then confrontation with the U.S. and Israel is inevitable. China should prepare a comprehensive plan and think about how to safeguard its own interests in event of such a catastrophe – which might well result in regime change in Tehran.