Thinkhubstudio

China’s government is finally moving to stimulate the economy after its sluggish post-COVID reopening. The country faces a slew of problems, including low consumer confidence, plummeting property sales, and high youth unemployment.

Even if the government succeeds in reviving the economy, investors may have to come to terms with structurally lower growth, a backdrop that calls for a much more selective approach to China’s equity markets.

Why did the Chinese economy not rebound as expected after the post-COVID reopening in December 2022? What is your outlook for China’s economic performance in 2024?

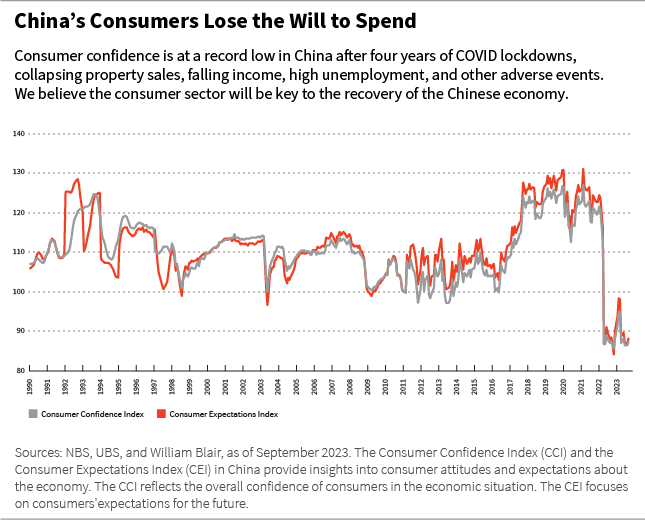

Vivian Lin Thurston: The main reason China hasn’t followed the post-COVID path of other countries is that consumer and business confidence is at an all-time low. This is understandable. The country was in lockdown for four years, longer than the rest of the world, and then saw a series of stop-start openings.

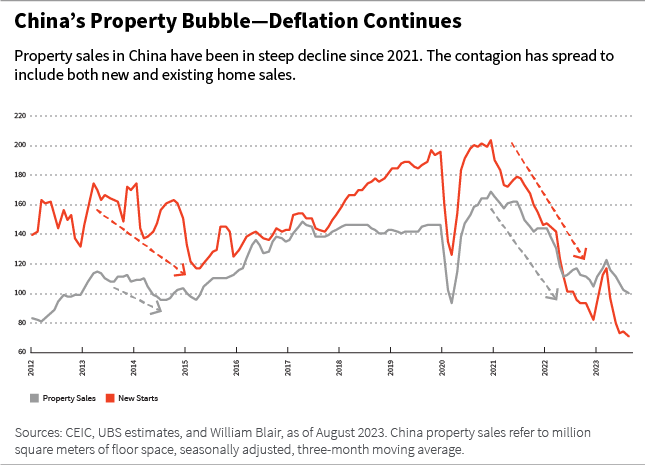

In addition, many Chinese tie their wealth to their property holdings, and property markets have experienced a severe downturn, with new home floor-space sales down 20% to 30% in 2023 following a 30% to 40% decline in 2022. This has created a negative wealth effect.

Weak employment and income recovery post-reopening has further exacerbated low confidence levels. The propensity to consume has been severely curtailed, and people have kept saving instead of spending.

The lack of a government stimulus has also not helped. In a confidence-led downward spiral, you need money to come in and jumpstart the real economy. It was not until recently that the government came out with a meaningful stimulus – a 1 trillion renminbi package announced in October 2023.

The absence of effective countercyclical measures over the past year is partly explained by the fiscal weakness of local governments. Their finances were damaged by the huge cost of managing COVID and the decline in land sales, which tend to be the biggest source of local government revenue.

Another factor is a marginal shift of leadership’s focus away from economic growth toward structural reforms. And, of course, the Chinese economy is just bigger now, which makes it harder to stimulate.

Our view is that we are now at a cyclical bottom and will see a gradual economic recovery as stimulus flows through and as the base effect, or year-ago comparison, gets more favorable.

Clifford Lau: I agree with this. At the time of this writing, it looks as if we are still on track to achieve 5% GDP growth in 2023. At the same time, we see many pockets of weakness.

Manufacturing has been disappointing. The service sector is expanding, but at a slow pace. Exports have dragged, partly due to a soft global economy. Fixed asset investment has been weak. Private investors, domestic and global, appear to be concerned about regulatory risk. We think this is behind us, but it takes time to rebuild confidence.

Credit demand has also been weak, especially demand for longer-term credit, reflecting a lack of confidence. But the numbers are slowly improving after government efforts to boost the demand side of the property market, which include cutting mortgage rates and reducing banks’ reserve requirement ratios.

The 1 trillion renminbi stimulus package could be a game-changer, but there are a lot of holes to fill. One of those holes is a looming crisis in local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), which are private companies that borrow money from investors to fund local government initiatives.

LGFVs’ indebtedness could become a systemic risk if it is not carefully handled. It has grown too big for the central government to address with just a “debt-to-equity-swap” solution. It could weigh on economic growth for some time.

Despite all this, we expect the economy to perform better in 2024 because it will be coming off such a weak base.

How will the 1 trillion renminbi stimulus package be deployed?

Vivian: In late October, China announced it will issue 1 trillion renminbi in special central government bonds and transfer the funding directly to local governments to support infrastructure investments and post-disaster recovery amid recent floods in certain areas. The first tranche, 500 billion renminbi, will be disbursed and deployed by the end of 2023 and the rest in 2024.

The magnitude of this stimulus package and its fast deployment indicate the government’s determination to stabilize the economy. This stimulus should help strengthen local governments’ fiscal stability, stimulate the real economy, and repair consumer and business confidence, although the impact could be more gradual.

Clifford: To be clear, the government is not aiming to use stimulus money to directly support the property market. It is trying to address the fallout from local governments being so dependent on land sale revenues in the past.

Property market support will likely be second order and include lowering mortgage rates, redefining mortgage terms, and granting preferential credit. It is not the government’s priority to protect struggling property developers from their creditors.

How has the semiconductor industry in China been affected by U.S. government efforts to restrict its access to advanced technology? How should investors assess this risk?

Vivian: The recent U.S. executive order was aimed at preventing China from advancing in three key fields with national security implications: semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing.

One major move has been to block China’s access to high-performance semiconductor chips and related semiconductor equipment. The United States has been sanctioning and restricting China’s technology advancement for some time and has steadily tightened restrictions to capture not just cutting-edge technology but a much wider range of technologies.

However, many Chinese companies have continued to push forward and even accelerated their pursuit of technology advancement by already producing advanced chips.

While sentiment on this issue is negative, the real impact on Chinese companies is probably less than people expect. It will likely be felt more by global technology companies who supply China.

How should investors assess geopolitical risk in Chinese asset markets considering recent developments, like the heightened U.S.-China tensions and China’s “no-limits” relationship with Russia?

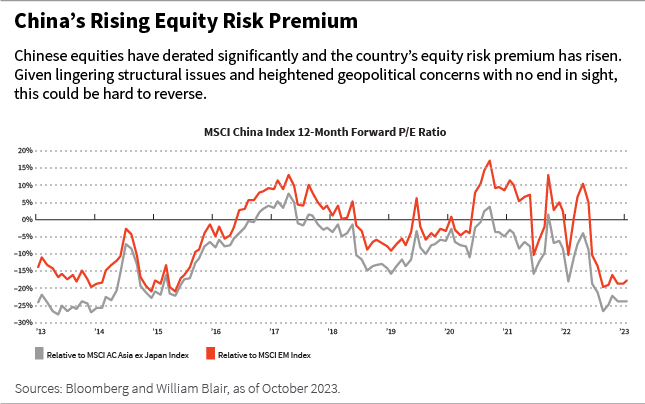

Vivian: Global investor sentiment towards China deteriorated in 2023. The United States and China are strategic competitors and that is unlikely to change. With every passing year, it plays out in different ways, but from an investor perspective, sentiment seems to be getting worse.

This shows up in a rising Chinese equity risk premium. Chinese equities derated tremendously in 2023. It was partly due to the cyclical downturn and partly due to lingering structural issues, but it was also due to increased geopolitical concerns.

As a result, the discount rate, or risk premium, for Chinese equities is higher. That could be hard to reverse without the improvement of any of the three factors mentioned above.

What should equity investors be looking for in 2024? Which parts of the Chinese economy seem the most attractive for quality growth investors?

Vivian: We have seen value strongly outperform growth for the past two years, given the weak and uncertain growth outlook of the Chinese economy, rising interest rates globally, and a risk-off mentality amid geopolitical risks and conflicts. This is a challenging backdrop for quality growth investors.

Although it is difficult to predict how this environment will shift, we continue to find and look for attractive companies and stocks with idiosyncratic drivers. As China’s economic growth structurally decelerates, we believe Chinese equity investment is becoming more of a bottom-up, stock-picking play than a top-down beta play.

The consumer segment will be critical as we look to 2024. If consumption revives and retail sales recover, this could be a bright spot, especially for companies with pricing power, strong brand positioning, and an unchanged structural growth story.

In industrials, high-end manufacturing continues to look attractive. Some sub-industries experienced near-term slowdowns linked to weaker end-markets in electric vehicles, green energy, and semiconductors, but they are structurally strong.

On the other hand, industrial machinery is more of a cyclical recovery story. It has a natural replacement cycle that was interrupted during COVID, so there is pent-up demand.

In tech hardware, the Chinese semiconductor industry is seeing improved fundamentals after a down cycle in the last couple of years. This was primarily due to weakness in end demand for consumer electronics and smartphones driven by a poor product cycle (similar to global smartphone markets), sanction-led supply constraints, and reduced consumer confidence and purchasing power as a result of prolonged COVID lockdowns.

However, as third quarter results come in, we are seeing early signs of a sequential order recovery and cycle bottoming. Over the long term, we believe the Chinese domestic semiconductor industry remains attractive, driven by structural share gains of domestic players considering their technology advancements.

Equity market performance in 2024 will depend on economic recovery, in our opinion. Many factors will need to align – confidence must improve, income to lower urban population groups must recover, and property markets must stabilize.

In addition, employment needs to rise, especially youth employment, which has been depressed by both weakness in the service sector due to an anemic economic reopening and in the internet industry due to regulatory measures.

What is the outlook for China’s bond market in 2024? Where do you see the best opportunities for fixed income investors?

Clifford: Our bond-market view is driven by our outlook for China’s economic growth. We expect it to be better going forward, but not dramatically so. As a result, interest rates are unlikely to rise significantly.

If anything, the government has reason to maintain low interest rates to keep financing costs affordable. Similarly, inflation does not seem to be a risk based on the latest numbers.

When it comes to investing in the Chinese bond market, we believe you must look at it in relative terms. At the time of this writing, the benchmark 10-year Chinese government bond is trading below 2.7%, whereas the U.S. Treasury 10-year bond has moved up to the mid- to high-4% range. That is more than 200 basis points of negative carry for a dollar-based investor.

We see little opportunity for capital gain other than miniscule carry gain, given China’s low interest rates. That leaves the currency element as a source of potential profit for global investors. But we don’t see major upside in the renminbi – the 12-month forward implied yield of CNH (the offshore renminbi) is less than 3%.

Perhaps one of the best opportunities could be for funds that deal in distressed debt. Most of the Chinese distressed property bonds are trading at single cents on the dollar.

If there is some major turnaround in the Chinese property market, it is possible to imagine appreciation from these low levels leading to outsized benefits for investors.

But we aren’t anticipating that the government will try to revive the property sector. In our opinion, it is more likely that it will continue to let the sector consolidate and de-lever in a market-driven way.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.