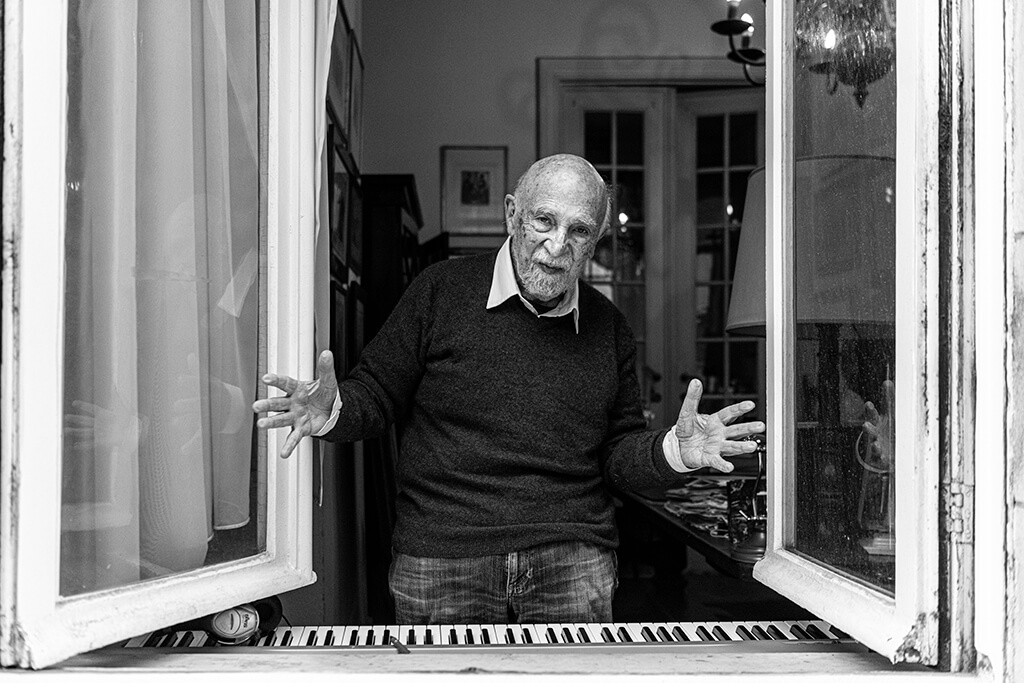

Ben Stern, San Francisco, 2019. Photo by Yuval Rakavy Israel, Courtesy of Lonka Project

I had stumbled into a gallery of complex, beautiful, elderly people: a woman smiling widely as she did a split on a periwinkle bedspread; a black-and-white of a smooth-skinned old man staring intensely into the camera in a sweater vest, button-down shirt, and tie; another man in a pinstriped suit flashing a radiant smile as he rolled up his left sleeve. The tattoo on the man’s forearm was testament to what each of these people shared: They are among the last living survivors of the Holocaust.

These people “not only just survived,” American photographer Jim Hollander, who helped curate the exhibition, told me the day after the reception. “They prospered.”

Hollander and his wife, Israeli photographer Rina Castelnuovoco-founded the Lonka Projecta collaboration between 311 photographers in 35 countries to create a visual record of European Jews who lived despite the Nazis’ attempts to exterminate them. On Wednesday, the Lonka Project displayed a selection of its photos in the lobby of the United Nations’ Visitor Center in New York City as part of an event titled “We’re Still Standing” in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27.

The art initiative is named after Hollander’s mother-in-law, Dr. Eleonara “Lonka” Nass, who survived five concentration camps in her childhood. Starting in 2019, as they grew alarmed at reports that younger generations were increasingly ignorant about the Holocaust, Hollander and Castelnuovo started inviting photographers from around the world to take pictures of Holocaust survivors on a volunteer basis. They had few instructions and were free to follow their instincts; most of them met repeatedly with survivors in order to get to know them, Hollander said.

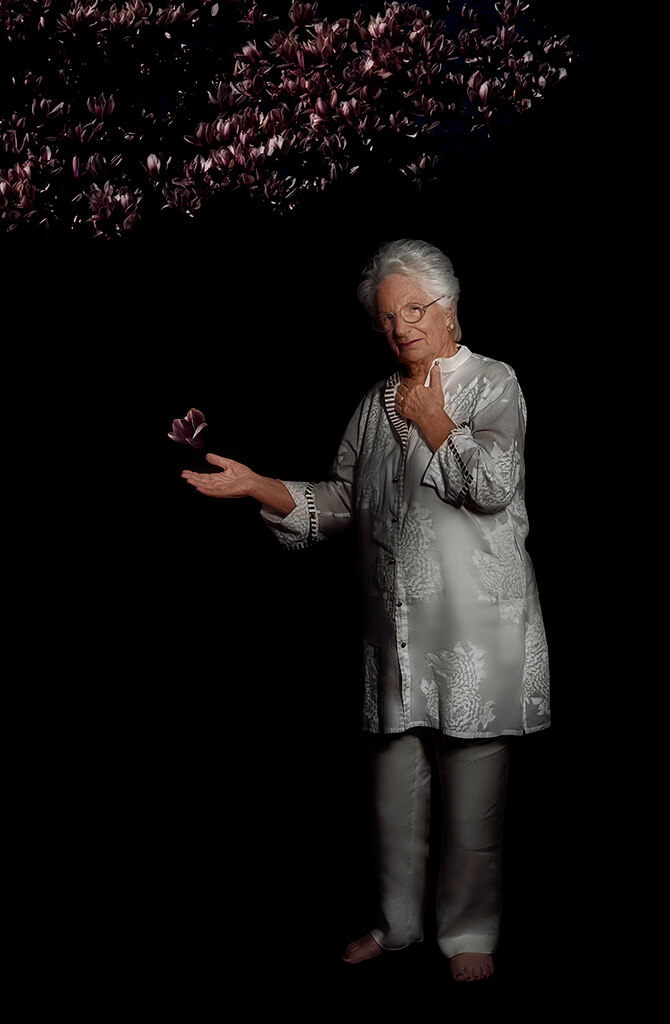

The result is a wide variety of intimate portraits that are striking in their dignity and vivacity. In Paris, the renowned Walter Spitzer, who passed away at age 93 due to complications from COVID-19, was photographed alongside a colorful painting of a Jewish scholar writing next to a pastoral landscape. In one of the more surreal photos, Italian politician Liliana Segre stands in a white tunic against a pitch-black sky, holding her hand out to reveal a floating, glowing leaf. These elders are more than survivors — they are guides.

“They’re very resolute people, very forgiving, very peace-loving, very compassionate,” said Hollander. “They almost all speak about, ‘Don’t hate anybody. Love anybody you come in contact with.’”

At the reception, I packed into a vaulted front hall to hear speakers connect the lessons of the Holocaust to our present moment. Among the more than one hundred attendees were the Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Palau ambassadors to the United Nations, and the speakers included Gilad Erdan, the Israeli Ambassador to the United Nations, and Nat Shaffir, a Holocaust survivor who often lectures at the United States Holocaust Museum.

Hamas’ October 7th terrorist attacks, in which more than 1200 Israelis, mostly civilians, were killed, loomed heavy over the speeches. The most gut-wrenching comparison between the recent attacks and the Holocaust was made in a short documentary filmed by the Lonka project and screened in the middle of the reception.

In the film, Holocaust survivors who themselves had been victims of the Oct. 7th attacks spoke candidly about their experiences. “It is a Shoah,” said Ruth Haran, a Romanian Jewish survivor — and Lonka project photo subject — who had settled in Kibbutz Be’eri and lost seven family members, including her daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, in the attacks. “I know how to internalize pain, but this time, the pain won’t go in.”

Ambassador Erdan said in his speech that Jewish resilience meant fighting for the Jewish state, including in the United Nations. The day before, when Erdan spoke at a UN Security Council Meeting, many diplomats walked out in protest of Israel’s siege on Gaza, where the Israel Defense Force has killed more than 25,000 Palestinians, the vast majority of them women and children. Just before the walkout, Riyad Al Maliki, Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Observer State of Palestine, pleaded for a ceasefiresaying, “We must make sure it stops now and we must make sure it never happens again,” in reference to violence against Palestinians. “Never again.”

At the reception for “We’re Still Standing,” Mr. Erdan struck a defiant tone. “We’re still standing,” he said. “Many have tried to destroy us, but all have failed and fallen and today will be no different.”

Hollander says he hopes that the Lonka project, which has just been collected into a book in Israel titled, The Lonka Project: The Power of Life that will soon be available in the United States, will inspire people to fight bigotry. Oct. 7 made “the work more pertinent and more important — especially the stories these people tell of putting a stop to ethnic hatred and having compassion.” Hollander said.

He emphasized that to truly benefit from the work, one needs to read the stories that accompany each photo in the book and on the Lonka project’s website. A reader might learn, as I did, that the man smiling with a rolled-up sleeve was Eddie Jaku, a German Jew who lost his parents to the Holocaust and himself survived Buchenwald concentration camp, escaped a Nazi death march, and hid in a forest until the end of the war, later rebuilding his life in Australia. He lived to the age of 101 and helped found the Sydney Jewish museum. He called himself “the happiest man on earth,” published a best-selling memoir by the same name, and vowed to smile to himself every day. His mantra, quoted on Lonka’s website, was a simple and timeless one: ‘I teach children and adults not to hate.’