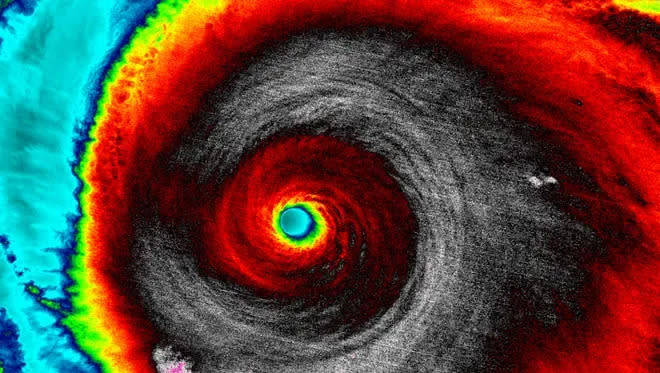

As fearsome as Category 5 hurricanes can be for people living in harm’s way, a new study reports global warming is supercharging some of the most intense cyclones with winds high enough to merit a hypothetical Category 6.

The world’s most intense hurricanes are growing even more intense, fueled by rising temperatures in the ocean and atmosphere, according to the study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. And, the authors say, a Category 5 on the traditional wind scale underestimates their dangers.

“As a cautious scientist, you never want to cry wolf,” said Michael Wehner, co-author and climate scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. But after searching for the signature of climate change in the world’s most intense cyclones, Wehner said he and co-author Jim Kossin found “the wolf is here.”

“Significantly increasing” temperatures, fueled by greenhouse gas emissions, up the energy available to the most intense tropical cyclones, reported Wehner and Kossin, a retired federal scientist and science advisor at the nonprofit First Street Foundation.

More cyclones are making the most of it, gaining higher wind speeds and more intensity, the authors said, and their evidence shows that will occur even more often as the world grows warmer.

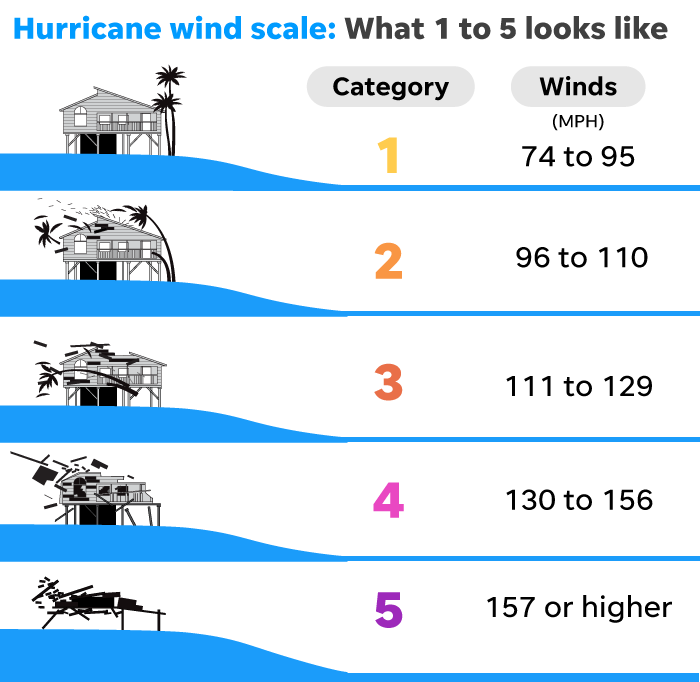

They used a hypothetical Category 6, with a minimum threshold of 192 mph, to study hurricanes that have occurred in the modern satellite era, since around 1980. They found five hurricanes and typhoons that would have met the criteria and all five occurred within the last decade.

To be clear, they aren’t proposing adding that category to the National Hurricane Center’s wind scale, which experts say would require a lengthy process and many partners. But they are hoping to “inform broader discussions about how to better communicate risk in a warming world,” Kossin told USA TODAY.

Their findings emphasize that the dangers associated with a Category 5 cyclone are increasing as storms intensify above the Cat 5’s 157-mph threshold and that results in an underestimation of risk, he said.

They found the chances of that potential intensity occurring in such storms have more than doubled since 1979. They say the areas where the growing risks of these storms are of greatest concern are the Gulf of Mexico, the Philippines, parts of Southeast Asia and Australia.

Their peer-reviewed, scientific research provides the evidence pointing to climate change that some scientists have been waiting for.

For more than 35 years, the scientific community has expected to see thermodynamic wind speeds increase in hurricanes, said Kerry Emanuel, the climate scientist who edited the paper for the journal. “And now we are seeing this increase in both climate analyses and models..”

What is the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale?

The hurricane center has used the well-known scale – with wind speed ranges for each of five categories – since the 1970s. The minimum threshold for Category 5 winds is 157 mph.

Designed by engineer Herbert Saffir and adapted by former center director Robert Simpson, the scale stops at Category 5 since winds that high would “cause rupturing damages that are serious no matter how well it’s engineered,” Simpson said during a 1999 interview.

The open-ended Category 5 describes anything from “a nominal Category 5 to infinity,” Kossin said. “That’s becoming more and more inadequate with time because climate change is creating more and more of these unprecedented intensities.”

A Category 6?

Scientists, including Kossin, have occasionally brought up adding another category to the scale for more than 20 years.

Climate scientist Michael Mann, director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability & the Media at the University of Pennsylvania, has argued for years that the Earth is “experiencing a new class of monster storms – ‘Category 6’ – hurricanes,” thanks to the effects of human-caused warming.

Mann wrote a commentary to the Wehner and Kossin study, published in the same journal Monday, saying their work lays out an objective case for expanding the scale to include the “climate change-fueled stronger and more destructive storms.”

“We are witnessing hurricanes that – by any logical extension of the existing Saffir-Simpson scale – deserve to be placed in a whole separate, more destructive category from the traditionally defined (category 5) ‘strongest’ storms,” Mann wrote.

The research adds to a growing discussion about how the center, emergency managers and others could better convey the full range of hazards from a major hurricane.

Climate change Is it fueling hurricanes in the Atlantic? Here’s what science says.

Hurricane scale doesn’t measure other, greater risks

The Saffir-Simpson scale only describes the wind risk and does not account for coastal storm surge and rainfall-driven flooding, the two biggest killers in hurricanes.

Adding a sixth category to the wind scale wouldn’t help address those concerns, Kossin said.

The hurricane center has tried to steer the focus toward the individual hazards, including storm surge, wind, rainfall, tornadoes and rip currents, Jamie Rhome, the center’s deputy executive director, said last week. “So, we don’t want to over-emphasize the wind hazard by placing too much emphasis on the category.”

Despite the center’s efforts, the storm’s wind category always gets the most attention from the public when a storm approaches.

“That focus on category over the years has detracted from effective communication of the other hazards,” said James Franklin, a retired branch chief for hurricane specialists at the hurricane center. “The emphasis at the NHC, rightly, has been to focus on the hazards,” he said.

Ultimately, the decision would likely rest with the center, but Kossin said the conversation would “have to happen over time with a lot of input” from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, social scientists and others.

It’s likely the World Meteorological Organization would be asked to weigh in because of the international scope involved in hurricane and typhoon forecasting, Franklin said. That’s the same group that sets the list of hurricane names for each season.

To Franklin, the question is what would a sixth category accomplish?

“If there are things that emergency managers would do differently, or the public might do differently because a storm has 195 mph winds versus 160 mph winds, then maybe the categories should be changed,” he said. “Personally, I’m getting out of the way if it’s 165 mph winds or 195 mph winds.”

Which storms fit the study’s hypothetical Category 6 description?

One hurricane in the eastern Pacific, Patricia, and four typhoons in the western Pacific:

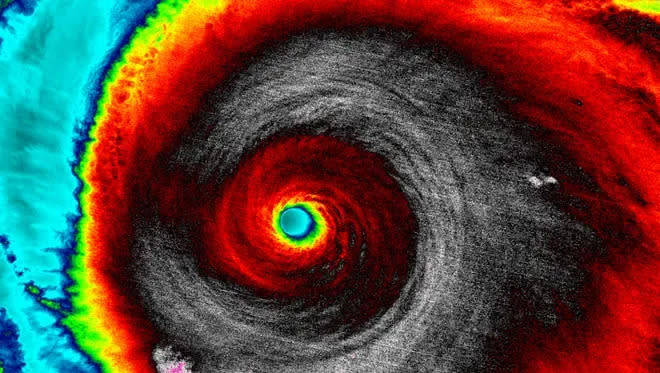

◾ Haiyan, November 2013: Struck the southern Philippines with 196-mph winds and a storm surge of almost 25 feet, killing 6,300 people and leaving 4 million homeless.

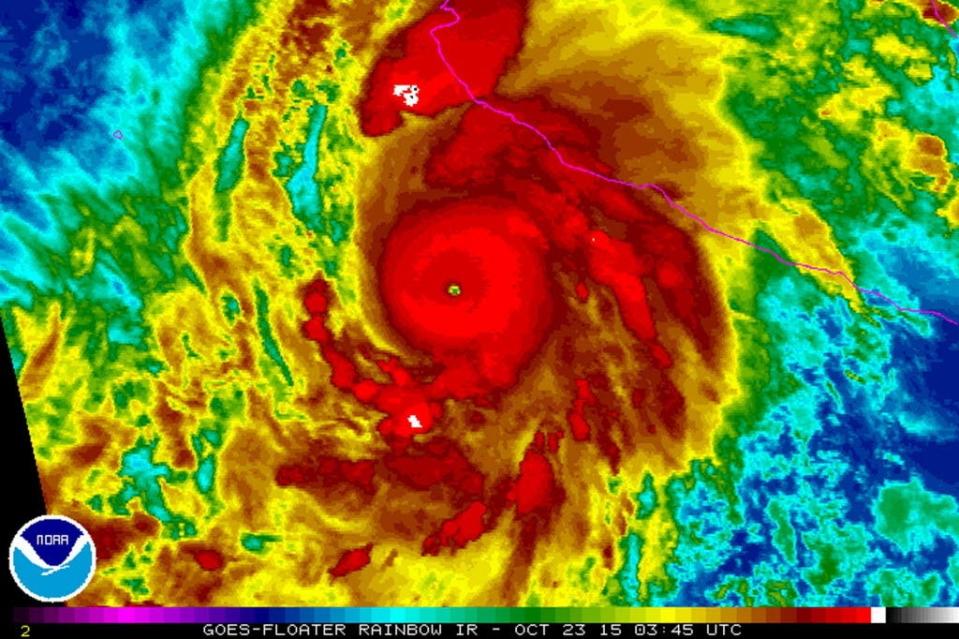

◾ Patricia, October 2015: Reached winds of 216 mph at sea, then dropped before it made landfall in Jalisco, Mexico as a Category 4 storm.

◾ Meranti, September 2016: Moved between the Philippines and Taiwan before making landfall in eastern China. Its winds reached 196 mph.

◾ Goni, November 2020: Made landfall in the Philippines with winds estimated at 196 mph.

◾ Surigae, April 2021: Reached wind speeds of 196 mph over the ocean, tracking east of the Philippines. Its max winds were the highest ever recorded for a storm from January to April anywhere in the world.

Dinah Voyles Pulver covers climate and environmental issues for USA TODAY. Reach her at dpulver@gannett.com or @dinahvp.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Category 6 hurricane? That’s what a new study suggests. Here’s why.