On the wall of my ex-husband’s office in downtown Johannesburg were pictures of serious-looking men, trade unionists who had fought for the rights of black workers in the darkest days of apartheid South Africa. Many of them were Jewish.

As were many of the leading figures of the struggle against apartheid rule, with the majority of the white ANC members predominantly Jewish. Yet that historically close relationship appears to have disintegrated after the recent South African decision to take Israel to the International Court of Justice accusing it of genocide against the Palestinians.

The image of South African president Cyril Ramaphosa wearing a typical Palestinian keffiyeh and ANC officials noisily welcoming the Court’s judgement – which stopped short of confirming the genocide accusation but was generally seen as anti-Israel – sent a collective shiver down the spines of the country’s 50,000-strong Jewish community.

Get The Jewish News Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories

Free Sign Up

Many are the children or grandchildren of people who had found shelter there from the Nazis’ advance, like my in-laws who had left Germany with just the clothes on the backs.

They started again from scratch and made a new life for themselves, like many new South Africans, grateful for having been given a second chance.

Julie Carbonara

Although most got down to work and chose not to rock the boat, a sizeable number of these first-generation Jewish South Africans ended up taking an active role in the fight against racial discrimination alongside the newly established African National Congress (ANC).

As members of a race that had been so discriminated against, they felt duty-bound to fight a regime that itself discriminated on the bases of race.

The roll-call of the Jews who fought alongside the ANC against apartheid boasts some illustrious names: Ruth First, Joe Slovo, Norman and Leon Levy, to name just a few. At the infamous 1963 Rivonia treason trial five of the 13 defendants were Jewish; the most prominent was ‘accused number 3’: Denis Goldberg who served 23 years in jail alongside Nelson Mandela. Mandela himself was ‘accused number 1’.

In the decades that followed, members of the Jewish intelligentsia didn’t let off: MP Helen Suzman was often a lone voice of dissent in the white parliament, while Nadine Gordimer’s books shone a light on a different, multicolour country. And let’s not forget those trade unionists whose pictures had caught my attention, who fought for the rights of black workers.

The roll-call of the Jews who fought alongside the ANC against apartheid boasts some illustrious names: Ruth First, Joe Slovo, Norman and Leon Levy, to name just a few.

Therefore the liberation of Nelson Mandela and the advent of black rule didn’t provoke a Jewish exodus: a few people I knew left South Africa, mainly for another sunny country, Australia rather than Israel, and mainly because they were worried about the economy. In the main, however, life went on as before and there was even a Jewish leader of the opposition, Tony Leon.

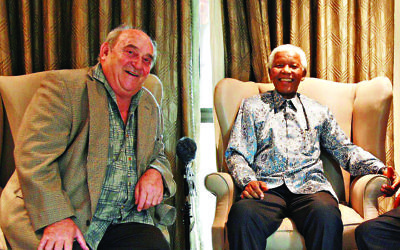

Denis Goldberg alongside Nelson Mandela. The pair spent 23 years in jail together.

Mandela himself never forgot the Jewish role in the black liberation struggle and managed a clever balancing act between supporting the Palestinian cause (the PLO had being a big supporter of the ANC) but also the right of Israel to exist. And, most importantly, he refused to have anything to do with Hamas and their ilk.

South African Jews had no reason not to feel safe. Until very recently, that is.

President Cyril Ramaphosa, who was a successful businessman before entering politics and apparently has many Jewish friends, is at pain to point out that he is anti-Zionist, rather than antisemitic.

Mandela never forgot the Jewish role in the black liberation struggle and managed a clever balancing act between supporting the Palestinian cause and Israel.

Whatever that might be, under his presidency South Africa has fully embraced the Palestinian cause casting Israel as the baddie that has implemented a modern-day apartheid, like the one the ANC fought so hard to defeat.

The genocide accusation is just the most recent chapter in this escalation but one that may make South African Jews question their future in the country.

Even for those who, like my South African family are not particularly religious or strong Zionists, the accusation feels like the worst type of betrayal. My father-in-law – who had had to leave Germany at 13 and refused to set foot there for the rest of his life – would have been horrified.

The celebratory reaction of some members of the South African government’s to the October 7 massacre may make many Jewish South Africans reassess their future in a country that seems to be pulling away from the West and western values.

South Africa has accused Israel – the only democracy in he Middle East – of genocide while at the same time edging closer to Iran whose financial support has been rumoured to be partially responsible for the shift.

Not a move that inspires confidence in the future.